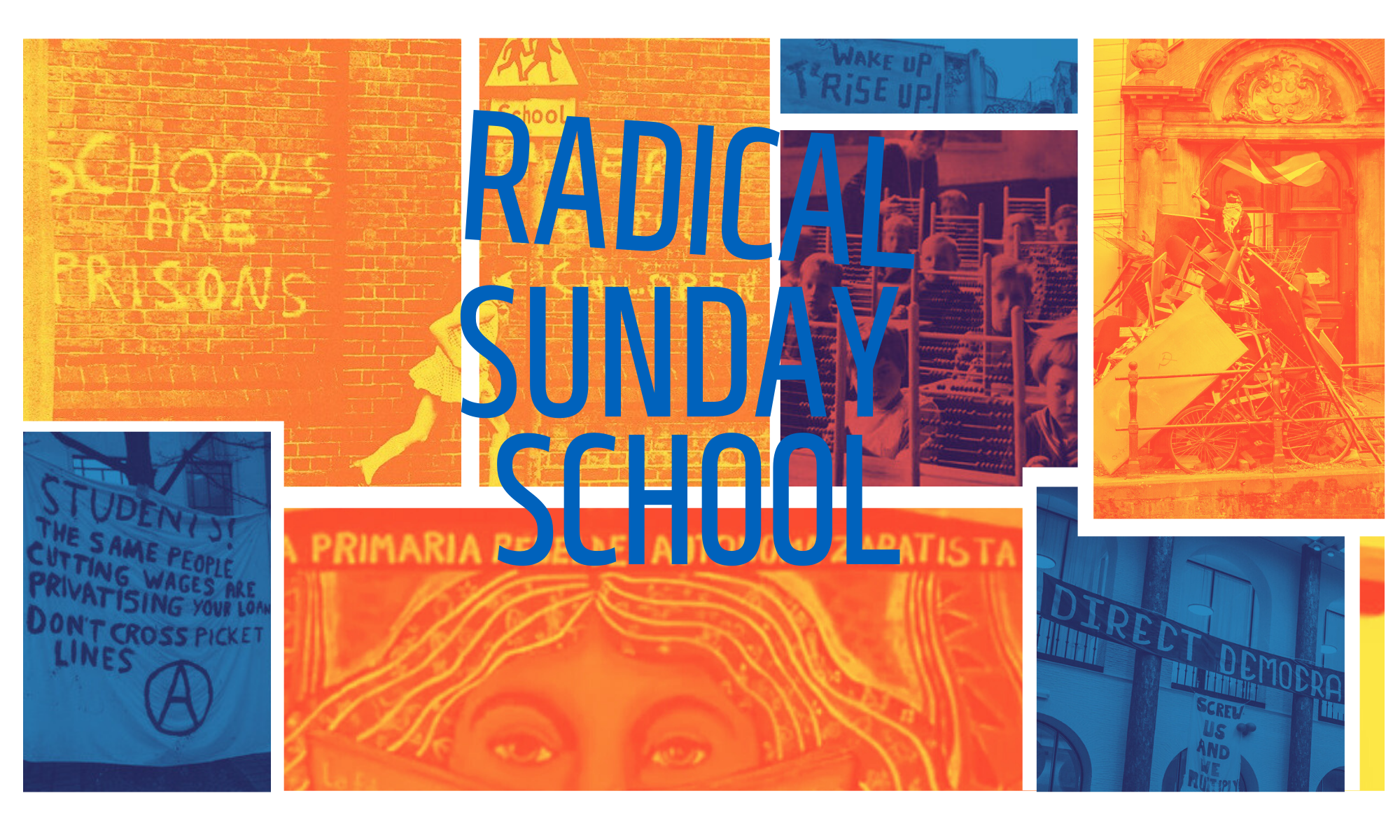

Beginning RSS

In the first session, we started off with a round discussion, initially on our experiences within education. It’s important to me that we decide together on what needs to be learned or explored, not that one person decides a set path for education. We can even think of it as a democratic way of study, an abolitionist approach to education, or possibly even – if you care to look this up – rhizomatic research, in which we can creatively explore alleys for active knowledge to emerge without a pre-set plan. Out discussion sprawled a bit (as can be expected in such a session) but we did come up with some themes that seem important to us in some way, from which we can build further sessions to collectively build a non-formal curriculum. For me personally, I would like to keep track of the three themes of the general UvA protests: Decolonisation, Democratisation, and Decarbonisation of the University.

The themes that emerged in the discussions, as I saw it (feel free to add also what you what you think I missed):

- The Narrative of Education

- We usually think of education as something pure, a bit romantic even, and we place incredible importance on it. We discussed also how often activists, who oppose many state or capital structures, have a soft spot for educational institutions. Is this justified?

- We also thought (and fought a little) over the role and privileges attached to an education. For some, a state education is a pleasantry, for others a necessity. Different standpoints to consider, especially if we are thinking across the differences on the planet.

- The Structural Role of Education

- What is the university’s position in the societal structure? How does it make systemic change possible, how does it prevent it also?

- What is the role of government in schools and universities, and what is the role of capital? What do we make of companies funding research and recruiting on campus?

- Education as something you need to pay for? As something that you ‘invest’ in? As something that trains you for employment or governance?

- How does this clash with the narratives of education?

- I would like to add to this – we didn’t get to it – that something else that’s interesting here is the presence of the police on campus. Cops off Campus campaigns are very interesting in this regard.

- The University over Time

- Very briefly we touched upon the university’s role in colonialism, its role in colonial domination

- We discussed the change of European universities from the post-war welfare state toward a faster, more specialised, and more individualised university in the era of neoliberalism; in particular, the Bologna Reforms that introduced the Bachelor/Master system across the EU. We were not in full agreement about whether this change was completely good or bad. On the one hand, the new university offers a freedom of choice not previously given, and on the other, old securities of education and lots of time were sacrificed. I have a feeling we can think this one much further, and tie it more to the structural role of the university.

An alternative educational vision – Weil and Grundtvig

The second half of the session, I gave my two cents on a different sort of educational vision. These centred on Simone Weil’s mystic education that centres on building attention. Weil, the coolest person in the European 20th century, and also one of its most useless people (highly recommend learning more about her person), thought of paying attention to the world’s affliction as passage of God acting through us, compelling us to be a vessel for the Good. She believed education and study were excellent tools to practice this kind of attention: education not only trains your cognitive skills and analytic abilities, but also directs your attention to what is important. With these considerations, you may wonder how attention to “evil” (in her Christian tongue) is hindered in today’s university. How come many of us are so educated but nevertheless participate in a harmful society? What is the point of understanding the world’s ills if you do not feel compelled to change them?

Through this lens, I shared some experiences of being education at a Danish Folk High School. These institutions, initially proposed as a university in the 19th century, I believe, by the scholar and pastor Grundtvig, centred on transformative, mystical, and democratising collective experiences. They use song, discussion, and fairly flat hierarchies to empower its students to become active citizens. The success of them over the time can be seen as a large chunk of the Danish population is part of an active civil society, and these schools were, for a long time, able to reach a broad majority (in an albeit small country, which is very rich now, but was also very, very poor for a long time). My time at this school was empowering, it felt like the options for action in the world were wider – just like Brazilian educator Paulo Freire believed education should be: a democratic back and forth in a community of learners, in which learners discover their place in the social reality, and turn into conscious and active participants willing to change this social reality. Putting all these together, I was thinking of schools as places of conversion: you go to a school to become something other than you are; learning is something that seeps into you, changes your subjectivity, the way you experience the world, what you pay attention to. But also, it doesn’t only happen in schools. Institutions do not have a monopoly on learning: It happens everywhere, all the time, and lies as a constant potential. Most of our learning happens in ‘life’, and its unstructured reality. There is a book I need to look into more for this, called Resonance Pedagogy by Hartmut Rosa.